Breast-Cancer

Predicting Breast Cancer Using Machine Learning

Imagine harnessing the power of machine learning to predict one of the most prevalent and life-threatening diseases: breast cancer. As data science enthusiasts, we often seek new challenges to expand our skills and dive into unexplored territories. This journey not only enhances our technical prowess but also broadens our understanding of diverse fields.

This article invites you to venture beyond the realms of digital marketing and media investment into the captivating world of healthcare. Did you know that cancer is the second leading cause of death globally, accounting for approximately 9.6 million deaths in 2018, according to the WHO. This staggering statistic underscores the urgent need for innovative solutions in early detection and treatment.

Join me as we explore how machine learning can be a game-changer in predicting breast cancer symptoms. We’ll utilize a comprehensive dataset from UCI, generously provided by academicians, to build our predictive model.

To bring this vision to life, we’ll employ powerful Python libraries like Pandas, Seaborn, and Scikit-learn. These tools will help us explore, clean, and visualize data, ultimately leading to a robust machine learning model. Ready to embark on this exciting adventure? Let’s break it down into manageable steps:

- Loading Libraries

- Data Exploration

- Data Visualization

- One Hot Encoding

- Feature Generation

- Data Splitting

- Machine Learning Modeling

- Data Prediction

Dive in and discover how you can leverage machine learning to make a meaningful impact in the fight against breast cancer.

1. Load Libraries

Much like any other data exploratory process in Pandas or Python, the initial phase involves loading the essential libraries into our working Jupyter Notebook environment. These libraries are the backbone of our data analysis and machine learning endeavors, providing us with the tools needed to manipulate, visualize, and model our data. Whether you’re using Jupyter Notebook, Google Colab, or Kaggle, the process remains largely the same. These platforms offer robust environments that support Python and its libraries, making them ideal for data science projects.

For this tutorial, I’ll stick to my faithful Jupyter Notebook environment, known for its versatility and user-friendly interface. Jupyter Notebook allows for an interactive data analysis experience, where code, visualizations, and explanatory text can coexist seamlessly. This setup will enable us to document our process comprehensively and adjust our code on the fly as we delve into the breast cancer dataset. While you’re free to use any Integrated Development Environment (IDE) you prefer, Jupyter Notebook’s integration with libraries like Pandas, Seaborn, and Scikit-learn makes it an excellent choice for this step-by-step guide.

import numpy as np # linear algebra

import pandas as pd # data processing, CSV file I/O (e.g. pd.read_csv)

import seaborn as sns # visualization library

1.1 Load Dataset

Start by creating a directory on your computer. Although I’m using a MacOS environment, the instructions provided here are applicable across different platforms. For the purpose of this walkthrough, let’s name the directory Project. This will serve as our main working directory. Navigate into the Project folder, as this will be our base for organizing and executing the steps outlined in this tutorial. The next step is to download the breast cancer dataset from the UCI site, which we’ll use for our machine learning model.

Within the Project directory, create a new folder named data and copy the downloaded CSV file into this data directory. This organization ensures that all relevant files are neatly stored and easily accessible throughout the tutorial. By structuring our project this way, we facilitate a smooth workflow and maintain order as we progress. Now that everything is set up, we can load the dataset into our Jupyter Notebook. This step allows us to examine, manipulate, and observe the data, laying the groundwork for our machine learning exploration.

df = pd.read_csv('data/breast_cancer_data.csv')

1.2 Dataset Size

Once we have completed the initial setup, we can proceed to analyze our dataset further. A common starting point in any data analysis project is to understand the size of the dataset. You might be wondering, just how large is our dataset? This question is easily answered using the .shape method in Pandas.

By applying the .shape method to our dataset, we can quickly obtain the number of rows and columns. This method returns a tuple representing the dimensions of the dataset, giving us an immediate sense of its scale. Understanding the size of our dataset is crucial as it informs us about the volume of data we will be working with and helps in planning subsequent data processing and analysis steps.

df.shape

(699, 12)

Rows & Columns

We can see we have the following information at hand:

- rows

699 - columns

12

1.3 Data Types

It’s always a good idea to get cozy with our dataset, not just by looking at its size, but by understanding what it’s really made of. Think of it like getting to know a new friend—you wouldn’t just ask them how tall they are, right? You’d want to know their quirks, their traits, what makes them tick. The same goes for our data. Knowing the types of data in each column helps us groove through the feature generation phase with ease.

So, let’s kick back and take a deeper dive. By checking out the data types of each column, we get the full picture: the numbers, the categories, the text. This insight is like the smooth rhythm of a jazz tune, guiding us to apply the right transformations and manipulations. When we’re in sync with our data, everything just flows better, leading to more accurate and reliable models. To get this vibe going, we’ll use the .dtypes attribute in Pandas. It’s our backstage pass to the inner workings of the dataset, giving us a clear overview of the structure and content. Let’s get jazzy with our data and see what it’s composed of!

# We need to observe the data types of each columns

df.dtypes

patient_id int64

clump_thickness float64

cell_size_uniformity float64

cell_shape_uniformity int64

marginal_adhesion int64

single_ep_cell_size int64

bare_nuclei object

bland_chromatin float64

normal_nucleoli float64

mitoses int64

class object

doctor_name object

dtype: object

1.3.1 The Data Legend

Let’s lay down the smooth beats of our dataset. Here’s the lowdown on the columns we have, as described by the source:

Patient ID: id numberClump Thickness: 1–10Uniformity of Cell Size: 1–10Uniformity of Cell Shape: 1–10Marginal Adhesion: 1–10Single Epithelial Cell Size: 1–10Bare Nuclei: 1–10Bland Chromatin: 1–10Normal Nucleoli: 1–10Mitoses: 1–10Class: malignant or benignDoctor name: 4 different doctors

So, what’s the vibe here? The Patient ID is our unique identifier, ensuring each record stands out. The Class column is the headline act, telling us whether the tumor is malignant (cancerous) or benign (not cancerous). The rest of the columns? They’re numeric medical descriptions of the tumor, except for Doctor name, which adds a categorical twist.

Keep this in mind—if our goal is to predict whether a tumor is cancerous based on the other features, we’ll need to perform some one-hot encoding on the categorical data and clean up the numerical data. Just like tuning an instrument before a jam session, prepping our data ensures everything flows smoothly in our analysis.

1.3.2 First & Last Rows

Now that we’ve got the lay of the land, let’s dive in and see what the top five records in our dataset look like. This peek at the first few rows will give us a quick feel for the data and help us spot any obvious issues or patterns right off the bat.

To do this, we’ll use the .head() method in Pandas, which will show us the first five rows. It’s like getting a sneak preview of the opening act before the main event. This simple step is crucial for ensuring we’re on the right track and that our data is ready to roll.

df.head()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Wong |

Additionally, checking the last few records with the .tail() method will give us a complete sense of the dataset’s structure. This combination of the first and last rows provides a balanced overview, ensuring no surprises lurk at the end. Let’s groove through the data and see what stories the top and bottom rows tell us!

df.tail()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | malignant | Dr. Lee |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Lee |

| 698 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 10.0 | 4.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Wong |

2. Descriptive Statistics

In Descriptive statistics, we are describing our data with the help of various representative methods using charts, graphs, tables, excel files, etc. In descriptive statistics, we describe our data in some manner and present it in a meaningful way so that it can be easily understood. Most of the time it is performed on small data sets and this analysis helps us a lot to predict some future trends based on the current findings. Some measures that are used to describe a data set are measures of central tendency and measures of variability or dispersion.

2.1 Numerical Analysis

Let’s jazz up our dataset with some sweet statistical insights! With the .describe() method, we’re about to dive deep into the numerical nitty-gritty. This little trick gives us the lowdown on key stats like count, mean, and standard deviation, shedding light on the distribution and central tendencies of our numeric data.

So, why does this matter? Well, getting cozy with these numbers gives us a clearer picture of what we’re working with. It’s like fine-tuning our instruments before a performance—it ensures our analysis hits all the right notes. With these stats in hand, we can groove through our dataset with confidence, uncovering hidden patterns and trends along the way. Let’s crank up the volume and see what the numbers have to say! 🎶

df.describe()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 6.990000e+02 | 698.000000 | 698.000000 | 699.000000 | 699.000000 | 699.000000 | 695.000000 | 698.000000 | 699.000000 |

| mean | 1.071704e+06 | 4.416905 | 3.137536 | 3.207439 | 2.793991 | 3.216023 | 3.447482 | 2.868195 | 1.589413 |

| std | 6.170957e+05 | 2.817673 | 3.052575 | 2.971913 | 2.843163 | 2.214300 | 2.441191 | 3.055647 | 1.715078 |

| min | 6.163400e+04 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 25% | 8.706885e+05 | 2.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 2.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 50% | 1.171710e+06 | 4.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 3.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 75% | 1.238298e+06 | 6.000000 | 5.000000 | 5.000000 | 3.500000 | 4.000000 | 5.000000 | 4.000000 | 1.000000 |

| max | 1.345435e+07 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 |

2.2 Categorical Analysis

Just like tuning into a different frequency, let’s shift our focus to the categorical side of the spectrum. With the .describe(include=['O']) method, we’re about to unravel the mysteries of our categorical data. While the output might be a bit more concise compared to its numerical counterpart, it still packs a punch.

By honing in on the categorical variables—those with a data type of object—we gain valuable insights into their distribution and uniqueness. It’s like flipping through the pages of a well-worn record collection, each category offering its own distinct vibe.

So, why bother? Well, understanding the landscape of our categorical data sets the stage for deeper analysis. Just like a DJ crafting the perfect mix, these insights help us blend and remix our data with precision. With the .describe(include=['O']) method in hand, we’re ready to spin some categorical magic and uncover the stories hidden within our dataset. Let’s dive in and see what melodies await! 🎵

df.describe(include=['O'])

| bare_nuclei | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| count | 697 | 699 | 699 |

| unique | 11 | 2 | 4 |

| top | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe |

| freq | 401 | 458 | 185 |

3. Data Reshaping

Time to remix our data and give it a fresh new vibe! With the code snippet you’ve got in hand, we’re about to shake things up and reshape our dataset like never before. By grooving to the beat of df.groupby(by=['doctor_name', 'class']).count(), we’re taking our data on a whole new journey.

Picture this: we’re gathering our data around the DJ booth, grouping it by the soothing sounds of doctor_name and the electrifying beats of class. Then, we crank up the volume with the aggregation function, counting up the hits in each group. It’s like taking our dataset to a cool underground club, where every combination of doctor and class brings its own unique vibe.

Why does this matter? Well, reshaping our data in this way allows us to uncover fresh insights and patterns that might have been hidden before. It’s like remixing a classic track—same ingredients, but with a whole new flavor. So, grab your data and let’s hit the dance floor, because we’re about to reshape it into something truly groovy! 🎧💃

# This aggreates the data by its column names, then we pass the aggregation function (size = count)

df.groupby(by =['doctor_name', 'class']).count()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| doctor_name | class | ||||||||||

| Dr. Doe | benign | 127 | 127 | 126 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 126 | 126 | 127 | 127 |

| malignant | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 57 | 58 | 58 | |

| Dr. Lee | benign | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 119 | 121 | 121 |

| malignant | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |

| Dr. Smith | benign | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 |

| malignant | 74 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 74 | |

| Dr. Wong | benign | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 107 | 108 |

| malignant | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 |

df.groupby(by =['class', 'doctor_name']).count()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| class | doctor_name | ||||||||||

| benign | Dr. Doe | 127 | 127 | 126 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 126 | 126 | 127 | 127 |

| Dr. Lee | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 119 | 121 | 121 | |

| Dr. Smith | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 102 | |

| Dr. Wong | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 107 | 108 | |

| malignant | Dr. Doe | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 57 | 58 | 58 |

| Dr. Lee | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |

| Dr. Smith | 74 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 73 | 74 | 74 | 74 | |

| Dr. Wong | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 |

df.groupby(by =['bare_nuclei', 'class']).count()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | doctor_name | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bare_nuclei | class | ||||||||||

| 1 | benign | 386 | 386 | 386 | 386 | 386 | 386 | 383 | 385 | 386 | 386 |

| malignant | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| 10 | benign | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| malignant | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | |

| 2 | benign | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| malignant | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| 3 | benign | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| malignant | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | |

| 4 | benign | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| malignant | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | |

| 5 | benign | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| malignant | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| 6 | malignant | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 7 | benign | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| malignant | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| 8 | benign | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| malignant | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | |

| 9 | malignant | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| ? | benign | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| malignant | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

4. Data Cleaning

Alright, time to chill and tidy up our dataset! Now that we’ve wrapped up the early analysis phase, it’s onto the next groove: cleaning up our data. Picture this: your data rolls in with all sorts of shapes and sizes, like records in a crate waiting to be sorted. But the real magic happens when we polish it up, turning it into the complete and comprehensive masterpiece we need.

Sure, it’s like sifting through a crate of vinyl, each record with its own scratches and dust. But trust me, the best jams come from the cleanest cuts. By whipping our dataset into shape, we’re setting the stage for some serious feature engineering and analysis down the line. So, grab your data mop and broom, because we’re about to sweep away the dust and uncover the smooth grooves beneath. Let’s get cleaning! 🎶✨

4.1 Missing Records

Among one of the easiet way to identify whether or not your dataset has any missing data in them, would be to check them using the .isna() method and combine them with the .sum() function. It would in return, give you information on how many rows gone missing in your current dataset. Usually Pandas, would assing them with the value of NaN, but it can always be just a blank value in the record cell.

df.isna().sum()

patient_id 0

clump_thickness 1

cell_size_uniformity 1

cell_shape_uniformity 0

marginal_adhesion 0

single_ep_cell_size 0

bare_nuclei 2

bland_chromatin 4

normal_nucleoli 1

mitoses 0

class 0

doctor_name 0

dtype: int64

Good to know that the patient_id has 0 missing values, but as you may notice, others columns much like clump_thickness, cell_size_uniformity, bare_nuclei, bland_chromatin and normal_nucleoli, and to put them in total, there are 9 missing rows in the dataset.

4.2 How To Deal With?

The real question isn’t just about spotting the missing records and summing them up. The real jazz starts when you decide how to handle them before moving forward on your data wrangling journey. In this particular case, we’ve got a small amount of data with missing values—just 9 rows out of 699. That’s a mere 0.012, or less than 1% of the total dataset. With such a small fraction, I’m thinking we drop them like they’re hot, using the .dropna method. And while we’re at it, let’s break down the cool attributes that groove along with the .dropna method.

Axis: Decides if you’re dropping rows or columns.0means rows, while1goes for columns.How: Two vibes here—any or all. If you chooseall, it drops rows or columns that are completely empty. Opt forany, and it drops those with even a single missing value.Inplace: This one’s crucial. If you setinplace=True, changes will happen right on the DataFrame you’re working with. If it’sFalse(which is the default), the original DataFrame stays untouched, and a new one is returned.

So, let’s clean up those missing beats and keep the data flowing smoothly!

df.dropna(axis=0, how='any', inplace=True)

df

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Wong |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | malignant | Dr. Lee |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Lee |

| 698 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 10.0 | 4.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Wong |

690 rows × 12 columns

As you can see now, the rows number have been decreased, from 699 to 690, down with 9 records, but left us with clean dataset with no empty cells in them. Let move on to check them!

df.isnull().values.any()

False

4.3 Rechecking

Now that we’ve got our dataset shining bright with no empty records, we might still be wondering if there’s another way to double-check for any sneaky missing values. Good news, data groovers! There’s a slick method called .isnull that performs a boolean check, giving you a smooth true or false response to your inquiry. It’s like having a jazz soloist confirming every note is in place. So, let’s slide into it and make sure our dataset is as clean as a crisp vinyl record. Let’s do this! 🎷✨

4.4 Validating

So, our dataset’s looking sharp, but let’s not stop there. If you’re curious whether there are still any hidden empty cells lurking around, there’s a cool cat method called .isnull that’s perfect for the job. This boolean checker will let us know with a simple true or false if any values are missing. It’s like having an extra pair of ears in the studio, ensuring every beat is perfect. Let’s give it a spin and make sure everything’s in tip-top shape! 🎶🔍

df.isnull()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 1 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 2 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 3 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 4 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 694 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 695 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 696 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 697 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

| 698 | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False | False |

690 rows × 12 columns

So far, so groovy! From our dataset checks, everything’s coming back with False values, and that’s music to our ears. It means one thing: our dataset is spotless and ready to jam. With our data all tuned up, it’s time to move on to the next leg of our journey. So, let’s keep the rhythm going and dive into the next adventure. Onward to data greatness! 🎷✨

4.5 Duplicate Records

Alright, let’s jazz things up and hunt for those duplicate records! First, we need to investigate whether our dataset is hiding any duplicate grooves in the cell records. By getting on top of this early, we can dodge potential hurdles that might throw our analysis offbeat and introduce unwanted bias.

To kick off this detective work, we’ll use the .nunique method. This little gem will give us some solid pointers to detect any anomalies lurking in our dataset. We’ll start by grooving through the columns that are supposed to have unique identifiers—those special object datatype columns. In our case, it’s the patient_id column. So, let’s spin that record and see if we have any duplicates in the mix! 🎷🔍

df.nunique()

patient_id 637

clump_thickness 10

cell_size_uniformity 10

cell_shape_uniformity 10

marginal_adhesion 10

single_ep_cell_size 10

bare_nuclei 11

bland_chromatin 10

normal_nucleoli 10

mitoses 9

class 2

doctor_name 4

dtype: int64

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 690 entries, 0 to 698

Data columns (total 12 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 patient_id 690 non-null int64

1 clump_thickness 690 non-null float64

2 cell_size_uniformity 690 non-null float64

3 cell_shape_uniformity 690 non-null int64

4 marginal_adhesion 690 non-null int64

5 single_ep_cell_size 690 non-null int64

6 bare_nuclei 690 non-null object

7 bland_chromatin 690 non-null float64

8 normal_nucleoli 690 non-null float64

9 mitoses 690 non-null int64

10 class 690 non-null object

11 doctor_name 690 non-null object

dtypes: float64(4), int64(5), object(3)

memory usage: 70.1+ KB

We know for sure that our dataset is jamming with 690 rows and 12 columns (down from the previous 699). But hold on a second—when we dig into the groove, we find that patient_id only has 637 records. Something’s offbeat here, especially since patient_id should be our unique identifier. We should be seeing a solid 690 records, not just 637.

Time to put on our detective hats and investigate this mystery. There’s gotta be some duplication in the patient_id column messing with our flow. Let’s dive deep, spin those records backwards, and uncover where the duplicates are hiding. This dataset is about to get a clean remix! 🎷🔍

4.6 Duplicate Patients

Alright, buckle up, because we’re about to dive into the mystery of the duplicate patient_id records. Picture this: you’re flipping through your dataset like a detective, and suddenly, you stumble upon some suspicious duplicates. But fear not, because we’ve got just the solution to unravel this enigma.

We’re borrowing a slick move from the data science playbook, courtesy of the wizards over at Stack Overflow. This little trick is like shining a spotlight on the shadows, revealing all the duplicate items lurking in the shadows of our dataset. With this solution in hand, we’ll shine a light on those repeat offenders and get to the bottom of this duplication dilemma. So, get ready to crack the case and uncover the truth behind those duplicate patients! 🕵️♂️🔍

- borrow from https://stackoverflow.com/questions/14657241/how-do-i-get-a-list-of-all-the-duplicate-items-using-pandas-in-python

df[df.patient_id.duplicated(keep=False)].sort_values("patient_id")

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 267 | 320675 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Wong |

| 272 | 320675 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Smith |

| 575 | 385103 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 269 | 385103 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe |

| 271 | 411453 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Wong |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 560 | 1321942 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe |

| 660 | 1339781 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 661 | 1339781 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 672 | 1354840 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Wong |

| 673 | 1354840 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

98 rows × 12 columns

Alright, check this out: we’ve got a little situation on our hands. It seems like we’ve got 98 patient IDs making multiple appearances in our dataset. Some are showing up twice, while others are pulling off the triple play. Now, wouldn’t it be sweet if we could get the lowdown on exactly how many times each patient ID is making a cameo?

Well, guess what? We’re about to dive into the nitty-gritty and unravel this mystery. Picture this: we’re peeling back the layers of duplication, analyzing each instance to tally up the total count. It’s like detective work for data scientists—sleuthing through the numbers to uncover the truth. So, grab your magnifying glass and let’s crack this case wide open. We’re diving deep into the world of duplications, ready to count ‘em up and bring clarity to our dataset! 🕵️♂️🔍

4.7 Duplicate Records

Let’s analyze how many times a single patient_id value, was being recorded more than once, in the next table.

- borrow from https://stackoverflow.com/questions/38309729/count-unique-values-with-pandas-per-groups

df.patient_id.value_counts()

patient_id

1182404 6

1276091 5

1198641 3

897471 2

411453 2

..

1231706 1

1232225 1

1236043 1

1241232 1

809912 1

Name: count, Length: 637, dtype: int64

Surpisingly, some are getting recorded more than twice, some are even getting recorded 6 times. Let’s move on to the next steps on how to deal with them.

df.drop_duplicates(subset="patient_id", keep='first', inplace = True)

df # let's print them.

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Wong |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | 763235 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | malignant | Dr. Lee |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Lee |

637 rows × 12 columns

Great, the above code just left us with one clean and no duplicated rows of data. Now the records are down from 690 to 637. Now let’s check wheter their still duplicates from the previous list of patient_id we had queried earlier, let’s try the 1182404 patient_id string for that matter.

# let's check whether the 1182404 patient_id still has duplication.

df.loc[df['patient_id'] == 1182404]

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 136 | 1182404 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee |

df.isnull().values.any()

False

5. Visual Analysis

And they say, picture says a thousand words. And I couldn’t agree more with the statement, we as a human easily absorb information, through graphs, colors and visualization, in contrast to just plain numbers. In this section, let’s try to visualize our findings better.

There are numerous great visualization libraries out there for both Python and Pandas, but I’ve been experimenting with Seaborn for awhile, and found them somewhat easier to implement to our objectives. Here are some of the benefit of having Seaborn as your library of choice for visualtization as taken from the official homepage:

Seaborn aims to make visualization a central part of exploring and understanding data. Its dataset-oriented plotting > functions operate on dataframes and arrays containing whole datasets and internally perform the necessary semantic mapping and statistical aggregation to produce informative plots.

Here is some of the functionality that seaborn offers:

- A dataset-oriented API for examining relationships between multiple variables

- Specialized support for using categorical variables to show observations or aggregate statistics

- Options for visualizing univariate or bivariate distributions and for comparing them between subsets of data

- Automatic estimation and plotting of linear regression models for different kinds dependent variables

- Convenient views onto the overall structure of complex datasets

- High-level abstractions for structuring multi-plot grids that let you easily build complex visualizations

- Concise control over matplotlib figure styling with several built-in themes

- Tools for choosing color palettes that faithfully reveal patterns in your data

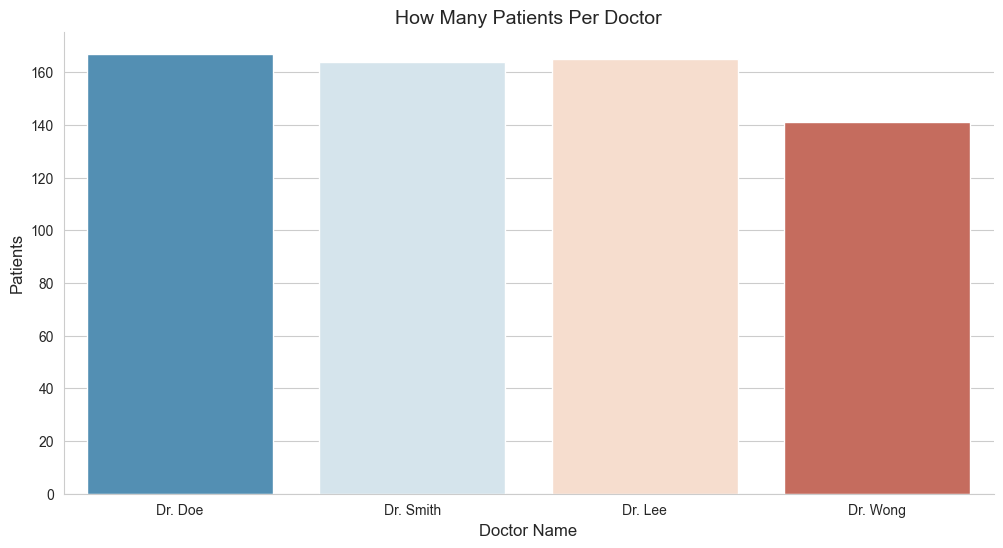

5.2 Patients for Each Doctor?

Ever wonder how many patients each doctor handled from the dataset? We know for sure, we have 4 doctors from the dataset, but haven’t got some perfect ideas on how many patients each doctor is handling them. So why don’t we try to visualize them, to see how many patients for each doctor needs to handle from the dataset?

df['doctor_name'].value_counts()

doctor_name

Dr. Doe 167

Dr. Lee 165

Dr. Smith 164

Dr. Wong 141

Name: count, dtype: int64

df['patient_id'].count()

637

# updated code

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import pandas as pd

# Define the dimensions of the figure

fig_dims = (12, 6)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=fig_dims)

# Set titles and labels

ax.set_title("How Many Patients Per Doctor", fontsize=14)

ax.set_xlabel('Doctor Name', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Patients', fontsize=12)

# Set Seaborn style and despine the plot

sns.set_style('whitegrid')

sns.despine()

# Create countplot

sns.countplot(x='doctor_name', hue='doctor_name', palette='RdBu_r', data=df, dodge=False, legend=False)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

Dr. Doe:167Dr. Lee:165Dr. Smith:164Dr. Wong:141

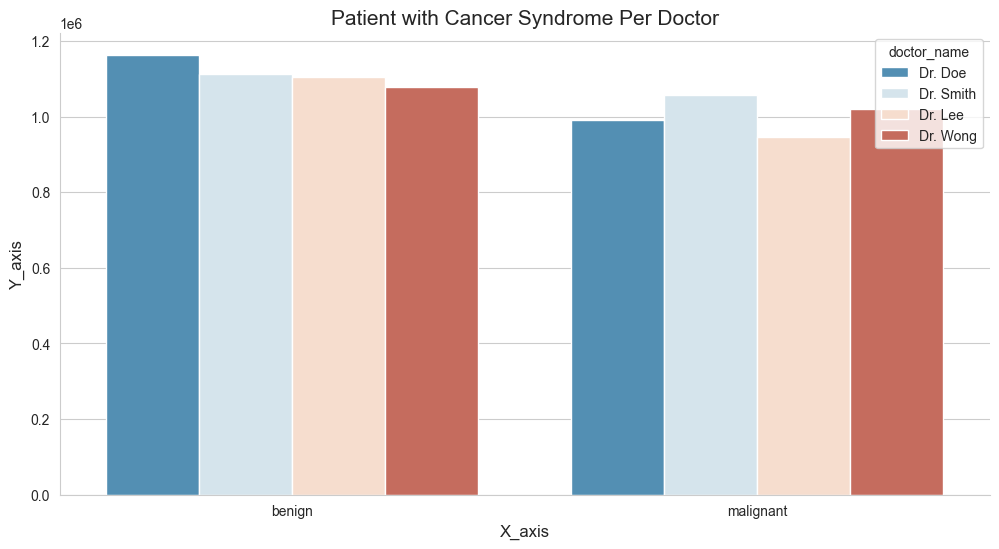

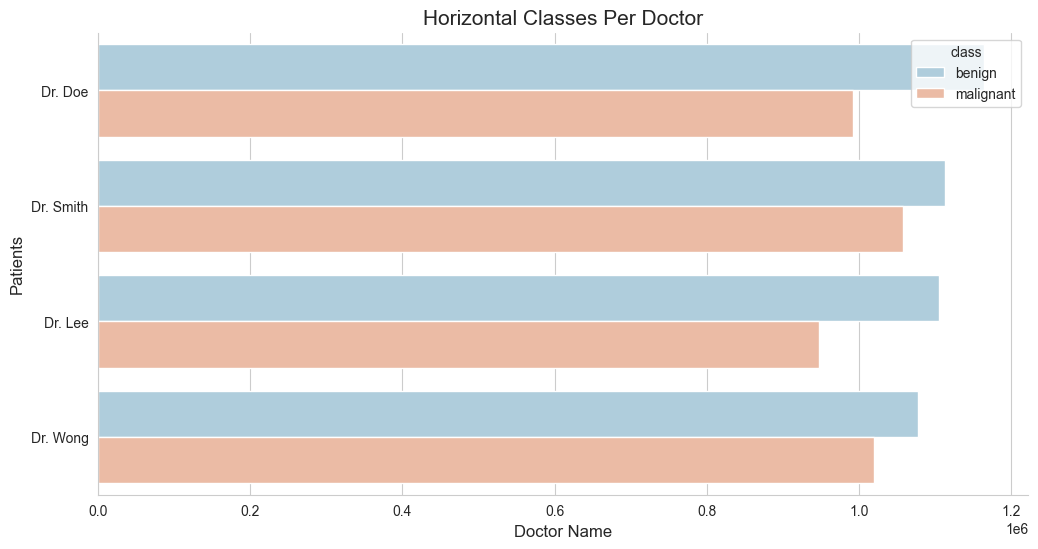

5.3 Class Cases For Each Doctor?

As mentioned on the earlier sections, we have a column name class, which basically contains the value of either benign and malignant. We wish to understand further whether a person’s tumor is malignant (cancerous) or benign (not cancerous). With that being said, let’s get down to business and try to visualize them further down below.

# Print the column names of the DataFrame to check for the correct column name

print(df.columns)

Index(['patient_id', 'clump_thickness', 'cell_size_uniformity',

'cell_shape_uniformity', 'marginal_adhesion', 'single_ep_cell_size',

'bare_nuclei', 'bland_chromatin', 'normal_nucleoli', 'mitoses', 'class',

'doctor_name'],

dtype='object')

df.columns = df.columns.str.strip()

print(df.columns)

Index(['patient_id', 'clump_thickness', 'cell_size_uniformity',

'cell_shape_uniformity', 'marginal_adhesion', 'single_ep_cell_size',

'bare_nuclei', 'bland_chromatin', 'normal_nucleoli', 'mitoses', 'class',

'doctor_name'],

dtype='object')

# class_by_doctor = df[("class")].value_counts()

# class_by_doctor

if 'class' in df.columns:

class_by_doctor = df['class'].value_counts()

print(class_by_doctor)

else:

print("The 'class' column is not present in the DataFrame.")

class

benign 407

malignant 230

Name: count, dtype: int64

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# updated code

fig_dims = (12, 6)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=fig_dims)

ax.set_title("Patient with Cancer Syndrome Per Doctor", fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('X_axis', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Y_axis', fontsize=12)

sns.despine()

sns.set_style('whitegrid')

sns.barplot(x="class", y="patient_id", hue="doctor_name", errorbar=None, palette='RdBu_r', data=df)

plt.show()

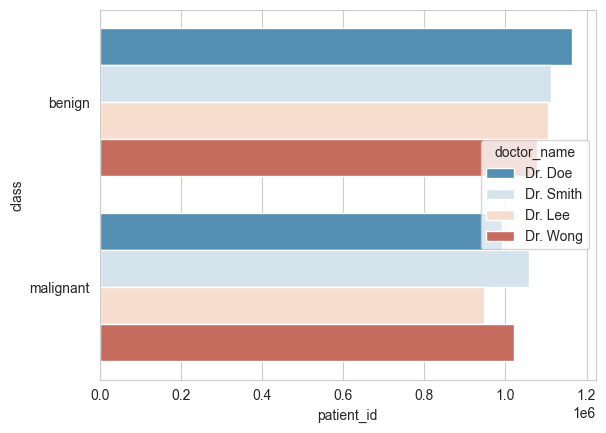

# This time, let's do them horizontally

# updated code

ax.set_title("Class of Patient Per Doctor", fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('Doctor Name', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Patients', fontsize=12)

sns.despine()

sns.set_style('whitegrid')

sns.barplot(x="patient_id", y="class", hue="doctor_name", errorbar=None, palette='RdBu_r', data=df)

plt.show()

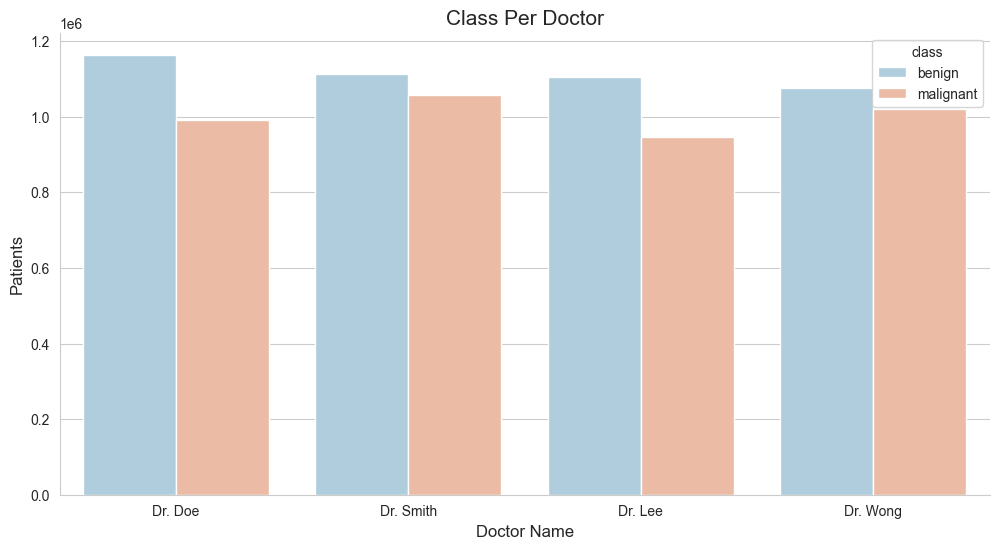

5.4 Class Case Per Doctor?

As mentioned on the earlier sections, we have a column name class, which basically contains the value of benign and malignant. We wish to understand further whether a person’s tumor is malignant (cancerous) or benign (not cancerous). With that being said, let’s get down to business and try to visualize them further down below.

# udpated code

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Define the figure dimensions

fig_dims = (12, 6)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=fig_dims)

# Set plot title and labels

ax.set_title("Class Per Doctor", fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('Doctor Name', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Patients', fontsize=12)

# Set style and despine

sns.set_style('whitegrid')

sns.despine()

# Create the barplot with the updated parameter

sns.barplot(x='doctor_name', y='patient_id', hue='class', errorbar=None, palette='RdBu_r', data=df)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

# updated code

fig_dims = (12, 6)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=fig_dims)

ax.set_title("Horizontal Classes Per Doctor", fontsize=15)

ax.set_xlabel('Doctor Name', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Patients', fontsize=12)

sns.despine()

sns.set_style('whitegrid')

sns.barplot(y='doctor_name', x='patient_id', hue='class', errorbar=None, palette='RdBu_r', data=df)

plt.show()

df.isnull().values.any()

df.isnull().sum().sum()

0

6. One Hot Encoding

Now that we’ve gone through the previous topic of visualizing our dataset, let’s continue to the next section of preparing them in a way that our machine learning algorithms, by which will be using them near the end of this article, would be able to pick them up and run them through our predictive model easily. You may ask, “Of all the previous process, they’re not enough?”. Well apparently, it’s not sufficient enough to meet the standards.

As among one of the challenges that we’re facing is still within the dataset itself. We’ll be better off by modifying them to meet the requirements. Our dataset still consist some categorical values in them, the doctors_name and class columns are two of good examples. And Machine Learning algorithm don’t normally like them. We need to modify these two columns, so that it would make it easier and less confusing for the machine learning model to process through. I came across this great example on how to deal with the similar situation.

6.1 doctor_name column.

Let’s first try to deal with the doctor_name column. This particular consist of 4 distinct values in them and how Pandas would handle them would probably as an object rather than an integer. Let’s have our work around for this particular area. Will create another variable and call it doctors_hotEncoded and use the get_dummies method to transform them to an encoded one.

doctors_hotEncoded = pd.get_dummies(df['doctor_name'])

doctors_hotEncoded

| Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | True | False | False | False |

| 1 | False | False | True | False |

| 2 | False | True | False | False |

| 3 | False | False | True | False |

| 4 | False | False | False | True |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | False | True | False | False |

| 694 | False | True | False | False |

| 695 | False | False | True | False |

| 696 | False | True | False | False |

| 697 | False | True | False | False |

637 rows × 4 columns

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df = pd.concat([df, doctors_hotEncoded], axis=1)

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | doctor_name | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Doe | True | False | False | False |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith | False | False | True | False |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee | False | True | False | False |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith | False | False | True | False |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Wong | False | False | False | True |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | 763235 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2 | benign | Dr. Lee | False | True | False | False |

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Lee | False | True | False | False |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | Dr. Smith | False | False | True | False |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | malignant | Dr. Lee | False | True | False | False |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | malignant | Dr. Lee | False | True | False | False |

637 rows × 16 columns

# Now let's drop the 'doctor_name' varibale

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.drop(columns=['doctor_name'])

# This is how it would look like.

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | True | False | False | False |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | benign | False | False | True | False |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | False | True | False | False |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | benign | False | False | True | False |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | False | False | False | True |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | 763235 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2 | benign | False | True | False | False |

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | False | True | False | False |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | benign | False | False | True | False |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | malignant | False | True | False | False |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | malignant | False | True | False | False |

637 rows × 15 columns

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().values.any()

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

0

6.2 class column.

# How to convert benign & malingant to 0 and 1

change_class_numeric = {'benign':0, 'malignant':1}

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['class'] = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['class'].map(change_class_numeric)

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | False | True |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | 763235 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | 1 | False | True | False | False |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False |

637 rows × 15 columns

#Making a new column based on a nuemrical calcualtion of other columns in the df

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['new_column'] = df.normal_nucleoli * df.mitoses

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.head()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | new_column | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 1.0 |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 2.0 |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 7.0 |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | False | True | 1.0 |

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().values.any()

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

0

7. Feature Generation

This is among the crucial aspect area of Machine Learning model in the article, as this article point out an individual might be classified as having a cancer if meet the following condtion:

- Their

cell_size_uniformityis greater than 5, and - Their

cell_shape_uniformityis greater than 5.

Based on this information, we could create another Feature from them.

# Feature building:

def celltypelabel(x):

if ((x['cell_size_uniformity'] > 5) & (x['cell_shape_uniformity'] > 5)):

return('1')

else:

return('0')

The code provided defines a function celltypelabel that takes a dictionary x as input and returns a string value based on the values of two specific keys within that dictionary: 'cell_size_uniformity' and 'cell_shape_uniformity'.

Here’s a step-by-step explanation of the function:

-

Function Definition:

def celltypelabel(x): ``` This defines a function named `celltypelabel` that takes one argument, `x`. -

Conditional Statement:

if ((x['cell_size_uniformity'] > 5) & (x['cell_shape_uniformity'] > 5)): ``` This is a conditional statement that checks two conditions: - The value of `'cell_size_uniformity'` in the dictionary `x` must be greater than 5. - The value of `'cell_shape_uniformity'` in the dictionary `x` must also be greater than 5. -

Logical AND Operator (

&): The logical AND operator (&) is used to combine these two conditions. Both conditions must be true for this part of the if-statement to evaluate to True. -

Return Statement:

return('1')If both conditions are met (i.e., both

'cell_size_uniformity'and'cell_shape_uniformity'are greater than 5), the function returns the string'1'. -

Else Clause:

else: return('0')If either or both conditions are not met (i.e., either

'cell_size_uniformity'or'cell_shape_uniformity'is not greater than 5), the function returns the string'0'.

Then we use the pandas apply function to run the celltypelabel(x) function on the dataframe.

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['cell_type_label'] = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.apply(lambda x: celltypelabel(x), axis=1)

The code snippet provided is used to apply the celltypelabel function to each row of the combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df DataFrame. Here’s a breakdown of what this code does:

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['cell_type_label'] = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.apply(lambda x: celltypelabel(x), axis=1)

7.1 Explanation:

- Apply Method: The

.apply()method is used to apply a function to each row or column of a DataFrame. - Lambda Function: A lambda function is used to define the function to be applied. In this case, it calls the

celltypelabelfunction. - Axis=1: The

axis=1parameter specifies that the function should be applied to each row (as opposed to each column, which would beaxis=0).

7.2 Step-by-Step Breakdown:

-

Define the Lambda Function:

lambda x: celltypelabel(x)This defines a lambda function that takes a dictionary

xand calls thecelltypelabelfunction. -

Apply the Lambda Function to Each Row:

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.apply(lambda x: celltypelabel(x), axis=1)This applies the lambda function to each row of the DataFrame. The result of this application is a new Series where each element is the output of the

celltypelabelfunction for that corresponding row. -

Assign Result to New Column:

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['cell_type_label'] = ...The result of applying the lambda function is assigned to a new column named

'cell_type_label'in the DataFrame.

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df[['patient_id', 'cell_type_label']]

| patient_id | cell_type_label | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 0 |

| 1 | 1002945 | 0 |

| 2 | 1015425 | 0 |

| 3 | 1016277 | 1 |

| 4 | 1017023 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | 763235 | 0 |

| 694 | 776715 | 0 |

| 695 | 841769 | 0 |

| 696 | 888820 | 1 |

| 697 | 897471 | 1 |

637 rows × 2 columns

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | new_column | cell_type_label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 1.0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 2.0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 7.0 | 1 |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | False | True | 1.0 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 693 | 763235 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 2.0 | 0 |

| 694 | 776715 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 | 0 |

| 695 | 841769 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 1.0 | 0 |

| 696 | 888820 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 2 | 1 | False | True | False | False | 20.0 | 1 |

| 697 | 897471 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False | 6.0 | 1 |

637 rows × 17 columns

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().values.any()

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

0

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.describe()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | new_column | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 6.370000e+02 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 | 637.000000 |

| mean | 1.076689e+06 | 4.488226 | 3.210361 | 3.298273 | 2.897959 | 3.284144 | 3.516484 | 2.971743 | 1.629513 | 0.361068 | 7.197802 |

| std | 6.408652e+05 | 2.855856 | 3.080628 | 3.007153 | 2.924191 | 2.243639 | 2.470924 | 3.146200 | 1.783293 | 0.480688 | 16.037352 |

| min | 6.163400e+04 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 25% | 8.779430e+05 | 2.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 2.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 50% | 1.173235e+06 | 4.000000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 3.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 75% | 1.238464e+06 | 6.000000 | 5.000000 | 5.000000 | 4.000000 | 4.000000 | 5.000000 | 4.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 6.000000 |

| max | 1.345435e+07 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 10.000000 | 1.000000 | 100.000000 |

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().values.any()

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

0

pd.crosstab(combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['class'], combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['cell_type_label'])

| cell_type_label | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| class | ||

| 0 | 404 | 3 |

| 1 | 118 | 112 |

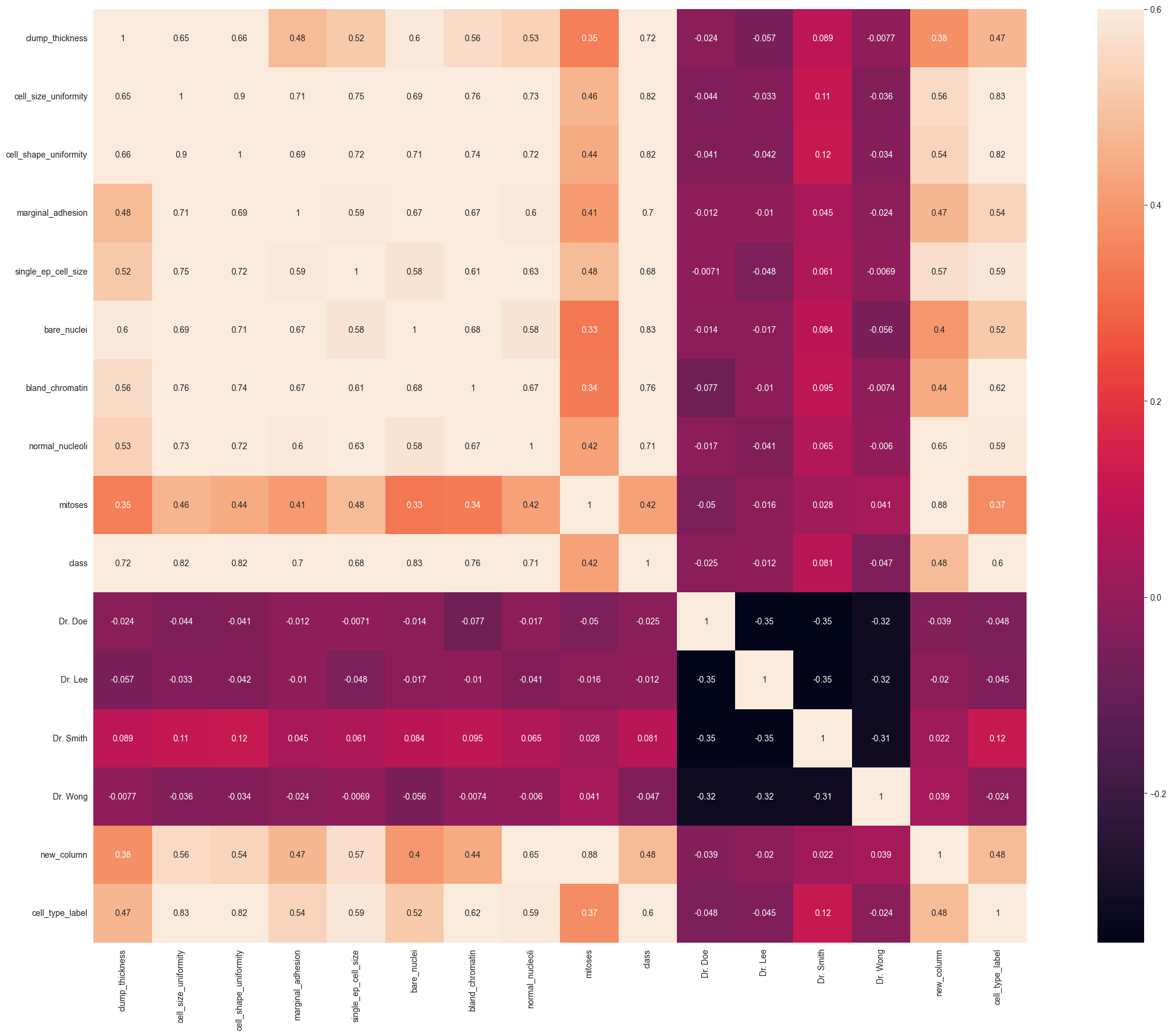

8. Correlating Features

Heatmap of Correlation between different features:

Positive= Positive correlation, i.e. increase in one feature will increase the other feature & vice-versa.

>Negative= Negative correlation, i.e. increase in one feature will decrease the other feature & vice-versa.

In our case, we focus on which features have strong positive or negative correlation with the Survived feature.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Handle non-numeric values: Replace '?' with NaN and convert columns to numeric

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.replace('?', np.nan, inplace=True)

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.apply(pd.to_numeric, errors='coerce')

# Drop 'patient_id' column and compute the correlation matrix

corr_matrix = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.drop('patient_id', axis=1).corr()

# Plot the heatmap

plt.figure(figsize=(30, 20))

plt.xlabel("Values on X axis")

plt.ylabel('Values on Y axis')

sns.heatmap(corr_matrix,

xticklabels=True,

vmax=0.6,

square=True,

annot=True)

plt.show()

9. Updating Data Types

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 637 entries, 0 to 697

Data columns (total 17 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 patient_id 637 non-null int64

1 clump_thickness 637 non-null float64

2 cell_size_uniformity 637 non-null float64

3 cell_shape_uniformity 637 non-null int64

4 marginal_adhesion 637 non-null int64

5 single_ep_cell_size 637 non-null int64

6 bare_nuclei 621 non-null float64

7 bland_chromatin 637 non-null float64

8 normal_nucleoli 637 non-null float64

9 mitoses 637 non-null int64

10 class 637 non-null int64

11 Dr. Doe 637 non-null bool

12 Dr. Lee 637 non-null bool

13 Dr. Smith 637 non-null bool

14 Dr. Wong 637 non-null bool

15 new_column 637 non-null float64

16 cell_type_label 637 non-null int64

dtypes: bool(4), float64(6), int64(7)

memory usage: 72.2 KB

# Let's try to change the datatypes of the following column in the dataset.

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['cell_type_label'] = combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['cell_type_label'].astype('float64')

# Let's try to change the datatypes of the following column in the dataset.

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['bare_nuclei'] = pd.to_numeric(combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.bare_nuclei, errors='coerce')

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().values.any()

True

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

16

np.all(np.isfinite(combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df))

False

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

16

# The bare_nuclei still has NaN or empty values in them?

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df['bare_nuclei'].describe()

count 621.000000

mean 3.631240

std 3.675234

min 1.000000

25% 1.000000

50% 1.000000

75% 7.000000

max 10.000000

Name: bare_nuclei, dtype: float64

# delete the empy rows

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.dropna(axis=0, how='any', inplace=True)

np.any(np.isnan(combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df))

False

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.isnull().sum().sum()

0

np.all(np.isfinite(combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df))

True

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 621 entries, 0 to 697

Data columns (total 17 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 patient_id 621 non-null int64

1 clump_thickness 621 non-null float64

2 cell_size_uniformity 621 non-null float64

3 cell_shape_uniformity 621 non-null int64

4 marginal_adhesion 621 non-null int64

5 single_ep_cell_size 621 non-null int64

6 bare_nuclei 621 non-null float64

7 bland_chromatin 621 non-null float64

8 normal_nucleoli 621 non-null float64

9 mitoses 621 non-null int64

10 class 621 non-null int64

11 Dr. Doe 621 non-null bool

12 Dr. Lee 621 non-null bool

13 Dr. Smith 621 non-null bool

14 Dr. Wong 621 non-null bool

15 new_column 621 non-null float64

16 cell_type_label 621 non-null float64

dtypes: bool(4), float64(7), int64(6)

memory usage: 70.3 KB

combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df.head()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | new_column | cell_type_label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000025 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 1002945 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 1015425 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 1016277 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 7.0 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 1017023 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | False | True | 1.0 | 0.0 |

10. Spliting Dataset

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Assuming combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df is your DataFrame

train, test = train_test_split(combined_doctors_hotEncoded_df, test_size=0.2)

# No need to convert to DataFrame as train_test_split returns DataFrames if the input is a DataFrame

train = pd.DataFrame(train)

test = pd.DataFrame(test)

# Displaying first few rows of train and test DataFrames to verify

print("Train DataFrame:")

print(train.head())

print("\nTest DataFrame:")

print(test.head())

Train DataFrame:

patient_id clump_thickness cell_size_uniformity cell_shape_uniformity \

304 653777 8.0 3.0 4

24 1059552 1.0 1.0 1

199 1214556 3.0 1.0 1

613 1016634 2.0 3.0 1

669 1350423 5.0 10.0 10

marginal_adhesion single_ep_cell_size bare_nuclei bland_chromatin \

304 9 3 10.0 3.0

24 1 2 1.0 3.0

199 1 2 1.0 2.0

613 1 2 1.0 2.0

669 8 5 5.0 7.0

normal_nucleoli mitoses class Dr. Doe Dr. Lee Dr. Smith Dr. Wong \

304 3.0 1 1 False True False False

24 1.0 1 0 False False True False

199 1.0 1 0 False True False False

613 1.0 1 0 True False False False

669 10.0 1 1 False False True False

new_column cell_type_label

304 3.0 0.0

24 1.0 0.0

199 1.0 0.0

613 1.0 0.0

669 10.0 1.0

Test DataFrame:

patient_id clump_thickness cell_size_uniformity cell_shape_uniformity \

582 1107684 6.0 10.0 5

520 333093 1.0 1.0 1

459 1267898 5.0 1.0 3

620 1083817 3.0 1.0 1

498 1204558 4.0 1.0 1

marginal_adhesion single_ep_cell_size bare_nuclei bland_chromatin \

582 5 4 10.0 6.0

520 1 3 1.0 1.0

459 1 2 1.0 1.0

620 1 2 1.0 2.0

498 1 2 1.0 2.0

normal_nucleoli mitoses class Dr. Doe Dr. Lee Dr. Smith Dr. Wong \

582 10.0 1 1 False True False False

520 1.0 1 0 True False False False

459 1.0 1 0 False True False False

620 1.0 1 0 False False True False

498 1.0 1 0 False True False False

new_column cell_type_label

582 10.0 0.0

520 1.0 0.0

459 1.0 0.0

620 1.0 0.0

498 1.0 0.0

# Now that we've managed to split our main combined dataset into train and test dataset, let's test them.

train.head()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | new_column | cell_type_label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | 653777 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False | 3.0 | 0.0 |

| 24 | 1059552 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 199 | 1214556 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 613 | 1016634 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 669 | 1350423 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | False | False | True | False | 10.0 | 1.0 |

test.head()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | new_column | cell_type_label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 582 | 1107684 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False | 10.0 | 0.0 |

| 520 | 333093 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 459 | 1267898 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 620 | 1083817 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 498 | 1204558 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 | 0.0 |

train.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 496 entries, 304 to 483

Data columns (total 17 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 patient_id 496 non-null int64

1 clump_thickness 496 non-null float64

2 cell_size_uniformity 496 non-null float64

3 cell_shape_uniformity 496 non-null int64

4 marginal_adhesion 496 non-null int64

5 single_ep_cell_size 496 non-null int64

6 bare_nuclei 496 non-null float64

7 bland_chromatin 496 non-null float64

8 normal_nucleoli 496 non-null float64

9 mitoses 496 non-null int64

10 class 496 non-null int64

11 Dr. Doe 496 non-null bool

12 Dr. Lee 496 non-null bool

13 Dr. Smith 496 non-null bool

14 Dr. Wong 496 non-null bool

15 new_column 496 non-null float64

16 cell_type_label 496 non-null float64

dtypes: bool(4), float64(7), int64(6)

memory usage: 56.2 KB

test.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 125 entries, 582 to 614

Data columns (total 17 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 patient_id 125 non-null int64

1 clump_thickness 125 non-null float64

2 cell_size_uniformity 125 non-null float64

3 cell_shape_uniformity 125 non-null int64

4 marginal_adhesion 125 non-null int64

5 single_ep_cell_size 125 non-null int64

6 bare_nuclei 125 non-null float64

7 bland_chromatin 125 non-null float64

8 normal_nucleoli 125 non-null float64

9 mitoses 125 non-null int64

10 class 125 non-null int64

11 Dr. Doe 125 non-null bool

12 Dr. Lee 125 non-null bool

13 Dr. Smith 125 non-null bool

14 Dr. Wong 125 non-null bool

15 new_column 125 non-null float64

16 cell_type_label 125 non-null float64

dtypes: bool(4), float64(7), int64(6)

memory usage: 14.2 KB

11. Machine Learning

11.1 Feature Selection

We drop unnecessary columns/features and keep only the useful ones for our experiment. Column patient_id is only dropped from Train set because we need patient_id in Test set while for running the experimentation.

train = train.drop(['patient_id', 'new_column'], axis=1)

test = test.drop('cell_type_label', axis=1)

11.2 Classification & Accuracy

Define training and testing set

# Importing Classifier Modules

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.svm import SVC, LinearSVC

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.naive_bayes import GaussianNB

from sklearn.linear_model import Perceptron

from sklearn.linear_model import SGDClassifier

train.head()

| clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | cell_type_label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False | 0.0 |

| 24 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 0.0 |

| 199 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 0.0 |

| 613 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 0.0 |

| 669 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | False | False | True | False | 1.0 |

test.head()

| patient_id | clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | new_column | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 582 | 1107684 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False | 10.0 |

| 520 | 333093 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False | 1.0 |

| 459 | 1267898 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 |

| 620 | 1083817 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False | 1.0 |

| 498 | 1204558 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False | 1.0 |

X_train = train.drop('cell_type_label', axis=1)

y_train = train['cell_type_label']

X_test = test.drop(["patient_id", "new_column"], axis=1).copy()

X_train.shape, y_train.shape, X_test.shape

((496, 14), (496,), (125, 14))

X_train.to_csv('train.csv', encoding='utf-8', index = False)

X_test.to_csv('test.csv', encoding='utf-8', index = False)

X_train

| clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False |

| 24 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 199 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| 613 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False |

| 669 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | False | False | True | False |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 291 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False |

| 155 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | True | False | False | False |

| 240 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 3 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 483 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | True | False | False | False |

496 rows × 14 columns

y_train

304 0.0

24 0.0

199 0.0

613 0.0

669 1.0

...

291 0.0

155 0.0

240 0.0

3 1.0

483 1.0

Name: cell_type_label, Length: 496, dtype: float64

X_test

| clump_thickness | cell_size_uniformity | cell_shape_uniformity | marginal_adhesion | single_ep_cell_size | bare_nuclei | bland_chromatin | normal_nucleoli | mitoses | class | Dr. Doe | Dr. Lee | Dr. Smith | Dr. Wong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 582 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | False | True | False | False |

| 520 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | True | False | False | False |

| 459 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| 620 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

| 498 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 277 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | False | True |

| 74 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3 | 1 | False | False | False | True |

| 152 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 1 | 1 | True | False | False | False |

| 136 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | True | False | False |

| 614 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 0 | False | False | True | False |

125 rows × 14 columns

11.3 Logistic Regression

Logistic regression, or logit regression, or logit model is a regression model where the dependent variable (DV) is categorical. This article covers the case of a binary dependent variable—that is, where it can take only two values, “0” and “1”, which represent outcomes such as pass/fail, win/lose, alive/dead or healthy/sick. Cases where the dependent variable has more than two outcome categories may be analysed in multinomial logistic regression, or, if the multiple categories are ordered, in ordinal logistic regression.

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

# Scale the data

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train)

X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test)

# Train the logistic regression model

clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=1000, solver='lbfgs')

clf.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train)

# Predict and calculate accuracy

y_pred_log_reg = clf.predict(X_test_scaled)

acc_log_reg = round(accuracy_score(y_train, clf.predict(X_train_scaled)) * 100, 2)

print(str(acc_log_reg) + '%')

97.78%

11.4 Support Vector Machine (SVM)

Support Vector Machine (SVM) model is a Supervised Learning model used for classification and regression analysis. It is a representation of the examples as points in space, mapped so that the examples of the separate categories are divided by a clear gap that is as wide as possible. New examples are then mapped into that same space and predicted to belong to a category based on which side of the gap they fall.

In addition to performing linear classification, SVMs can efficiently perform a non-linear classification using what is called the kernel trick, implicitly mapping their inputs into high-dimensional feature spaces. Suppose some given data points each belong to one of two classes, and the goal is to decide which class a new data point will be in. In the case of support vector machines, a data point is viewed as a $p$-dimensional vector (a list of $p$ numbers), and we want to know whether we can separate such points with a $(p-1)$-dimensional hyperplane.

When data are not labeled, supervised learning is not possible, and an unsupervised learning approach is required, which attempts to find natural clustering of the data to groups, and then map new data to these formed groups. The clustering algorithm which provides an improvement to the support vector machines is called support vector clustering and is often used in industrial applications either when data are not labeled or when only some data are labeled as a preprocessing for a classification pass.

In the below code, SVC stands for Support Vector Classification.

clf = SVC()

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred_svc = clf.predict(X_test)

acc_svc = round(clf.score(X_train, y_train) * 100, 2)

print (acc_svc)

97.78

11.5 Linear SVM

Linear SVM is a SVM model with linear kernel.

In the below code, LinearSVC stands for Linear Support Vector Classification.

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.svm import LinearSVC

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

# Scale the data

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train)

X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test)

# Train the Linear SVC model

clf = LinearSVC(dual='auto', max_iter=1000)

clf.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train)

# Predict and calculate accuracy

y_pred_linear_svc = clf.predict(X_test_scaled)

acc_linear_svc = round(accuracy_score(y_train, clf.predict(X_train_scaled)) * 100, 2)

print(acc_linear_svc)

97.78

11.6 $k$-Nearest Neighbors